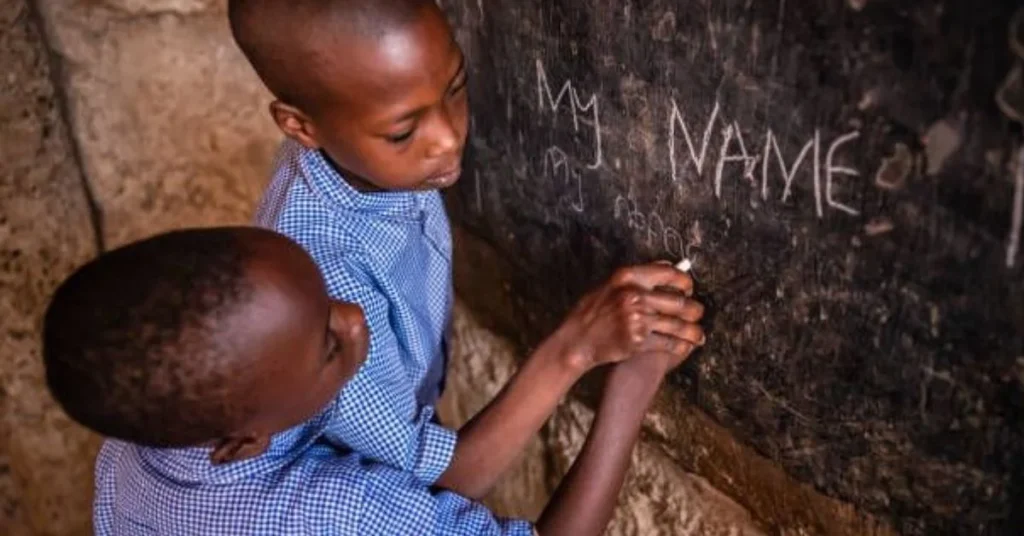

Education is the cornerstone of development, opportunity, and equality in any society. It has the power to lift entire generations out of poverty, reduce inequality, and improve the overall well-being of a nation. In Africa, where economic challenges, political instability, and social disparities have historically posed barriers to development, the importance of education cannot be overstated. Kenya and Sudan, two African countries with rich but contrasting histories, offer a compelling comparison in terms of access to education. While Kenya has made significant strides in improving education access over the past few decades, Sudan continues to struggle with systemic barriers, some rooted in conflict, governance issues, and deeply entrenched socio-cultural norms.

This article delves into the key reasons why access to education differs between Kenya and Sudan. We will explore the historical context, political environment, economic factors, social structures, gender roles, infrastructure, government policies, and international influence. The aim is to present a nuanced understanding of what drives the educational disparities between the two nations, why they persist, and what can be done to address them.

Historical Background: Foundations That Define the Present

Understanding the roots of educational access in Kenya and Sudan requires a look into their colonial and post-colonial histories. Both countries were colonized by the British, but their experiences and outcomes from colonial rule were markedly different, which has had a long-lasting effect on their educational systems.

In Kenya, the British colonial government introduced a more structured and centralized education system, particularly in urban areas and for communities that were seen as cooperative or economically viable. Missionary schools flourished, and by the time of independence in 1963, Kenya had already developed a foundational education framework. Although access was unequal and favored certain ethnic groups and regions, the groundwork was laid for future expansion.

In contrast, Sudan—which was jointly administered by Britain and Egypt—experienced a fragmented education system that received minimal investment. The northern part of Sudan received slightly better attention due to its geographic proximity to Egypt and relative political calm, but southern Sudan remained largely neglected, with very few schools and limited government oversight. The result was a grossly uneven education system that later contributed to tensions between the north and south.

After independence, Kenya continued to invest in education, building on the colonial framework, while Sudan faced internal divisions, civil wars, and regime changes that disrupted educational continuity. These divergent historical paths significantly contribute to the differences in educational access seen today.

Political Stability and Governance: Kenya and Sudan

One of the major factors that explain the difference in educational access between Kenya and Sudan is the level of political stability and governance.

Kenya, despite experiencing episodes of political unrest, has managed to maintain a relatively stable democratic framework. This stability has allowed successive governments to plan, implement, and fund long-term educational programs. For instance, the introduction of Free Primary Education (FPE) in 2003 by President Mwai Kibaki’s administration marked a major leap in educational access. The FPE policy abolished tuition fees for primary schools, resulting in a massive surge in school enrollment. Additionally, devolution under the 2010 Constitution enabled county governments to support local educational initiatives, further broadening access.

On the other hand, Sudan has been plagued by prolonged political instability, marked by coups, authoritarian rule, and civil conflict. The Sudanese Civil Wars, the secession of South Sudan in 2011, and ongoing internal conflicts in regions such as Darfur have severely undermined the education sector. Schools have been destroyed, teachers displaced, and government priorities diverted to military expenditures. Moreover, a lack of centralized planning and weak governance structures means that education policies are often poorly implemented, if at all. As a result, consistent access to quality education remains elusive for large portions of the Sudanese population.

Economic Capacity and Investment in Education

Economic strength and government investment play a vital role in educational development. Nations that allocate substantial resources toward education are more likely to see improvements in access, quality, and outcomes.

Kenya has one of the largest and most diversified economies in East Africa, which provides the government with more fiscal space to fund education. The country has consistently allocated a significant portion of its national budget to the education sector—often around 5-6% of GDP. These funds support teacher training, school infrastructure, curriculum development, and learning materials. Additionally, Kenya has embraced partnerships with international donors and NGOs to support marginalized communities and improve literacy rates.

In contrast, Sudan’s economy has been deeply affected by decades of conflict, international sanctions, and poor resource management. While Sudan is rich in natural resources such as oil, much of this wealth has not translated into public services, including education. Following the secession of South Sudan in 2011, Sudan lost nearly 75% of its oil revenue, leading to economic decline and inflation. As a result, the education sector suffers from chronic underfunding, low teacher salaries, inadequate school facilities, and lack of teaching materials. In many rural and conflict-affected areas, formal education is virtually non-existent.

Geographical and Infrastructural Challenges

The physical geography and infrastructure of a country can greatly influence access to education. Poor roads, lack of transportation, and harsh environmental conditions can make it difficult for children—especially those in rural areas—to attend school regularly.

In Kenya, while there are still infrastructural challenges in remote regions like Turkana or parts of northeastern Kenya, the country has made concerted efforts to build schools and improve road networks. Urban centers and many rural towns are served by relatively good infrastructure, which facilitates commuting and the delivery of educational materials. Moreover, Kenya has embraced technology in education, with digital learning programs being piloted in some areas.

In Sudan, particularly in the conflict-prone regions like Darfur, Blue Nile, and South Kordofan, schools are often located far from communities or are inaccessible due to insecurity and poor infrastructure. Floods during the rainy season, long distances between villages and schools, and lack of reliable transportation are common barriers. The situation is even worse in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, where temporary shelters serve as makeshift schools, lacking basic facilities such as toilets, electricity, or desks.

Cultural and Social Norms: Kenya and Sudan

Cultural beliefs, traditions, and societal norms significantly influence educational access, particularly for girls.

Kenya has made considerable progress in promoting gender equality in education, although disparities still exist in some regions. National campaigns, legal reforms, and community sensitization programs have emphasized the importance of educating girls. The government has also introduced sanitary towel distribution programs and policies against early marriage, which help keep girls in school. Though cultural practices like female genital mutilation (FGM) and early marriage still affect education in some communities, they are increasingly being challenged through advocacy and education.

In Sudan, deeply entrenched patriarchal norms and religious conservatism hinder educational access for girls. In many communities, especially in rural and war-affected areas, early marriage is prevalent, and girls are expected to prioritize domestic responsibilities over education. Religious and cultural beliefs may discourage girls from attending mixed-gender schools or receiving education beyond the primary level. Additionally, female teachers are often scarce, making it difficult to promote female education in conservative regions where parents prefer their daughters to be taught by women.

Language and Curriculum Differences: Kenya and Sudan

Language of instruction and curriculum relevance also affect education accessibility and effectiveness.

In Kenya, the language policy allows for mother-tongue instruction in early years, followed by transition to English and Kiswahili, the two official languages. This approach enhances comprehension in early childhood and prepares students for national exams conducted in English. Kenya’s curriculum has also evolved to include Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC), which focuses on skills development, creativity, and local relevance.

In Sudan, Arabic is the primary language of instruction, which can disadvantage non-Arabic-speaking communities, especially in the south and other marginalized areas. During Omar al-Bashir’s rule, the government pursued an aggressive Arabization and Islamization policy, which alienated non-Arabic-speaking populations and led to educational exclusion. Moreover, Sudan’s curriculum has often been criticized for being outdated, rigid, and not inclusive of diverse cultural identities, further marginalizing students from minority communities.

Role of International Organizations and NGOs

International support can be a crucial catalyst for improving educational access in developing countries.

Kenya has benefited immensely from international partnerships, including programs funded by the World Bank, UNICEF, UNESCO, USAID, and other bilateral donors. These programs have supported school feeding initiatives, construction of classrooms, training of teachers, and provision of learning materials. NGOs and faith-based organizations also play a prominent role in filling gaps, especially in marginalized communities like the arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs).

In Sudan, the work of international agencies has often been obstructed by political interference, conflict, and bureaucratic hurdles. Humanitarian organizations have provided emergency education in IDP camps and conflict zones, but these efforts are often short-term and unsustainable. In some cases, access has been denied altogether due to government restrictions or security concerns. This limited collaboration hampers the ability to reach children who are most in need.

Conflict and Displacement: Kenya and Sudan

Armed conflict is perhaps the most significant factor disrupting education in Sudan.

Kenya, while not entirely free of internal conflict, has not experienced war on the same scale as Sudan. Occasional ethnic clashes or terrorist threats, such as those by Al-Shabaab, have disrupted education temporarily in specific regions, but the overall education system remains intact.

Sudan, however, has been ravaged by multiple civil wars, intercommunal violence, and military coups. Entire regions have been depopulated due to violence, and schools have been destroyed or repurposed as military camps. Millions of children have grown up in refugee or IDP camps with little or no access to formal education. Trauma, psychological distress, and family disintegration further complicate their ability to learn. Even when peace agreements are signed, rebuilding the education infrastructure takes years, and trust in public institutions remains low.

Conclusion: Kenya and Sudan

The difference in educational access between Kenya and Sudan is not merely a reflection of geography or wealth; it is the result of a complex interplay of historical, political, economic, cultural, and infrastructural factors. Kenya’s relative stability, stronger governance, and proactive education policies have enabled it to expand access to education across much of the country. In contrast, Sudan’s long history of conflict, political turmoil, and socio-cultural barriers has created an environment where education is a luxury for many, rather than a guaranteed right.

Moving forward, bridging the gap in education access between the two countries requires both internal reform and international support. Sudan must prioritize peacebuilding, improve governance, invest in education, and promote cultural inclusion to make meaningful progress. Kenya, while ahead, must continue to address regional disparities and ensure that education quality keeps pace with access.

FAQs: Kenya and Sudan

1. Why is education more accessible in Kenya than in Sudan?

Education is more accessible in Kenya due to better political stability, consistent investment in the education sector, and proactive government policies like Free Primary Education. Sudan, in contrast, has faced long-term conflict and instability, which have severely disrupted its education system.

2. How does conflict affect education access in Sudan?

Conflict destroys infrastructure, displaces communities, and diverts government resources away from education. Schools are often closed or repurposed during conflict, and children living in conflict zones miss years of education, sometimes permanently.

3. What role does culture play in education access in both countries?

In Kenya, progressive cultural change and gender advocacy have improved education access, especially for girls. In Sudan, conservative norms and gender roles continue to restrict education for girls, particularly in rural and conflict-prone regions.

4. How do international organizations contribute to education in Kenya and Sudan?

International organizations play a vital role in funding, infrastructure development, and emergency education programs. Kenya has more open and effective collaboration with such bodies, while Sudan’s political and security challenges often limit their impact.

5. Can Sudan improve its education system in the future?

Yes, with political stability, increased investment, inclusive policies, and international cooperation, Sudan can improve its education system. Prioritizing peace and equitable development is key to sustainable educational reform.

For more information, click here.